So: driver and engine cooling, nimbler handling with more front adhesion, cleaner aerodynamics – all with the same rug¬gedness and reliability that have paid off before. Motor racing to Teddy Mayer is not to dazzle everyone with technology, it's to balance the books and keep faith with your sponsors by winning races. The M20 is a tool to do that job.

What's old and proven about it are the working bits: engine, transaxle, suspension, brakes, wheels. The engines are all big Reynolds aluminum blocks of 509 cu in. (4.5- by 4-in. bore and stroke) with detail improvements, pistons especially, to give about 750bhp and a better, flatter torque curve.

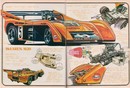

The gearbox is Hewland's strong big Mk II, as it was last year with the exception that it's the USAC version with a starting-motor shaft sticking out the back. This isn't for use with an external starter like Indy; it's because the new seat-back fuel tank prevents. access to the front of the engine when the mechanics want to turn it over. The 8in. spacer casting between engines and gearbox is hollow and does nothing but fill space, while Porsche on the 908/3 and Alfa Romeo have put their gearboxes in that empty space, and March tried it on the nix F1 car. Coppuck says the impossibility of changing gear ratios makes the amid¬ships gearbox impractical. The suspension members look as they did before. The geometry changes are due largely to the different arrangement of components, the longer wheelbase and wider track and such details as the chassis being about one inch shallower. The brakes continue trends begun late last season, in that the front discs are larger instead of being equal with the backs.

Late last year Revson's car had cross-drilled discs. but now they have found the same job can be done by machining grooves in the disc faces; typically there are three grooves per face running tangentially out from the hub to the edge. Their function is to prevent both pad dust and pad material "out-gassing" from interfering with friction.

The new chassis is bent up out of I6- and I9-9auge aluminum, riveted and bonded to itself as before, but this time the front suspension loads are taken not with a full steel bulkhead but by small steel brackets mounted on the tub. Yet the front of the chassis is designed to be stiffer than before. (There is no front radiator ducting/mounting structure to absorb collisions.) The shape of the tub is largely determined by the new radiator location, as fitting big enough cores takes up all the space right down to the bottom of the chassis. Therefore the outside edge of the fuel tanks had to be cut away at the rear to form a nice (and very carefully drawn) smooth air entry. It is this that produced the F1-style "Coke bottle" shape in plan view. To gain back the lost capacity an 18gal tank was put across the width of the car behind the driver's seat; it is actually the 5th fuel cell in the system, into which the other four (two per side) feed, and this new flow system helps position the several hundred pounds of liquid in the middle of the wheelbase as it burns off in a race.

The new car's body shape looks much like the old and in fact descends directly from it: the technique is to make up one more of the old body in extra heavy cloth, cut it into pieces and drape them over the new chassis, and then fill in the gaps to produce a male buck of the new body. The changes on the M20 are at the sides, where air is induced to flow into the radiators, and at the front where an airfoil rides in the gap between the wheel arches where the radiator ducting used to be – the radiator used to throw its exhaust air upward and produce downforce, but the airfoil does it more efficiently and is adjustable. Both drivers, incidentally, say there is no reduction in the buffeting of their heads from this air flow, but since it's cool air pouring over the top the cockpit, it is much more comfortable. A neat touch about the new nose is that it hinges up for access; furthermore, the struts that mount the hinge are adjustable for length and allow small adjustments in nose-rake angle.