|

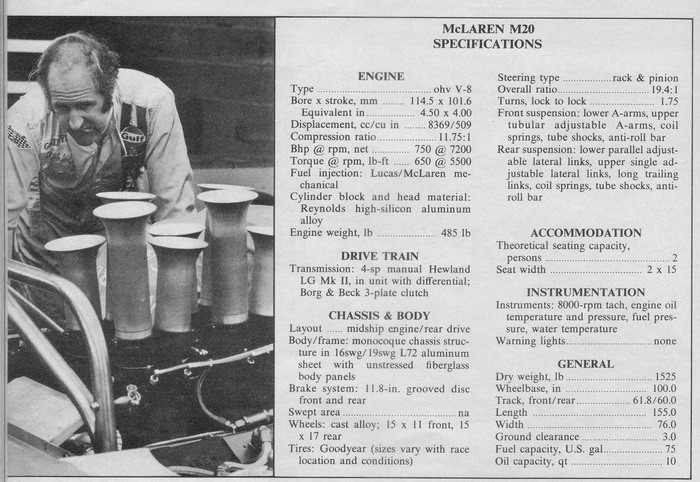

McLaren M20 The next stage of evolution as practiced by Can-Am's Establishment By Pete Lyons |

|

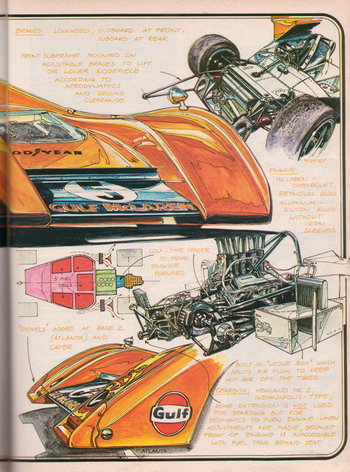

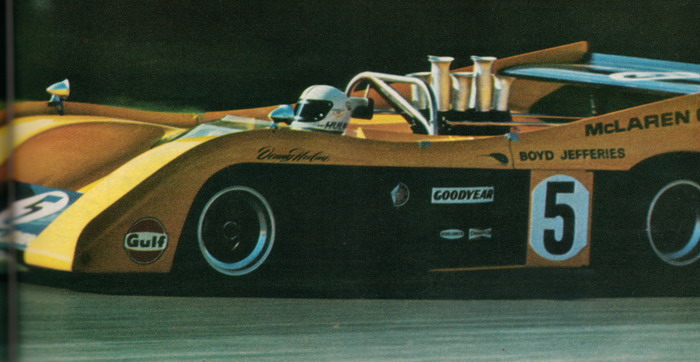

Although they usually manage to avoid producing camels, the men at the McLaren establishment operate as a committee when designing new cars. They are a conservative group-racing experience produces conservatism and don't seem the least bit sorry not to have a reputation for wild innovation. When they do lay down an all-new racer it's apt to draw heavily on what worked before. So it is with the M20. Most of the pieces are familiar and everything is good, sound, sturdy McLaren practice. Yet it is a much better car and seems to have achieved everything the committee wanted after teething troubles were sorted out. Gordon Coppuck: "We've taken great pains to get the weight distribution about the same as last year's car, but with a lower polar moment of inertia (Isn't that an Eskimo's tea break?) to produce a quicker and more predictable car. We've added two inches to the wheelbase, although there's an 8-in. spacer ahead of the gearbox which moves the engine up more toward the middle of the chassis. The driver has been moved forward as well, while the radiators are back amidship and the fuel is maintained in a more compact mass." Isn't much of this similar to last year's Lola T260 in layout? "I feel Eric made a mistake on that, doing it like a Formula I car. A slidey, throw-it-around sort of car. Our experience is that a Group 7 driver who throws it around is going to lose it. We prefer to have the car stick right down to the ground." Tyler Alexander: "The first thing we wanted to fix was a problem we'd had on the earlier cars. . . . I'm not going to say what it was." "Was it a matter of front-end adhesion?" " Ah . . . partly." Teddy Mayer: 'The first reason for the radiators in the sides is to lower the cockpit temperature, but it also allowed us to do more with the aerodynamics at the front, create more aerodynamic efficiency. And we got it, we were about I0 mph faster on the straight at Watkins Glen this year-about I92, I think. "Then we wanted zero change in the weight distribution between full and empty, and we've pretty well achieved that. There are some small geometry changes; the track and wheel�base are bigger. The car is about 25 lb lighter than last year's, and it's got a lower polar moment and also the weight distribution is changed; it's a little more toward the front. The roll centers are 'in-the-air'-above ground. There isn't any anti-dive. There is some anti-squat, about the same as last year or maybe a little more. The radiators are something like 25 or 30 percent bigger in area, not because they have to be when you put them on the side but because the M8F's cooling capacity was pretty marginal. "Gary's improved the engines quite a lot this year-at Mosport our engines weren't good but they are now. There's a little more horsepower and the torque is better, it's flatter, it doesn't drop off so much at high rpm. Peter Revson's impressions: "It's a better balanced car than the M8F and there's less understeer. Because the balance is better you're able to get out of the turns faster, get the horse�power down to the ground better coming out of the turns. I can't say I can really feel this 'lower polar moment' subjectively. But the cockpit is cooler, a lot cooler." Denny Hulme: "We wanted it to run cooler, that was the main thing-and it made all the difference at the Glen this time, I can tell you! And it's a faster, better balanced car. I don't know about the 'low polar moment' business; it's not something you can feel in the seat of your pants. What makes a race car quick is balance. What's happening at one end you want happening at both ends, even-steven. You want balance-else you'll fall off the high wire! "Basically there's no change in weight distribution between the start and finish. It's very good and it stays fairly neutral. Quite often in the FI car we've got that problem but not in the Can-Am car now. "And we've got some mighty brakes. That's mainly due to Lockheed; they've spent time with us getting big, light brakes. At first the pedal wasn't good enough, but it's slowly become better. The brakes are better, especially when you consider the work they do, the energy they have to absorb; it must be enormous, if you calculate it. "There are some geometry alterations, but I can't really describe what they are-close as I am I don't really take much notice, and an outsider wouldn't have any idea. You never know the effect subjectively of these things, it's just a quicker car or it isn't. Everything we've done has had a slight effect and it all adds up." So: driver and engine cooling, nimbler handling with more front adhesion, cleaner aerodynamics-all with the same rug�gedness and reliability that have paid off before. Motor racing to Teddy Mayer is not to dazzle everyone with technology, it's to balance the books and keep faith with your sponsors by winning races. The M20 is a tool to do that job.

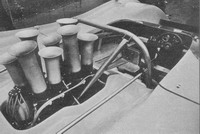

What's old and proven about it are the working

bits: engine, transaxle, suspension, brakes, wheels. The engines

are all big

Reynolds aluminum blocks of 509 cu in. (4.5- by 4-in. bore and

stroke) with detail improvements, pistons especially, to give about 750 bhp

and a better, flatter torque curve.

The gearbox is Hewland's strong big Mk II,

as it was last year with the exception that it's the USAC version with a

starting-motor shaft sticking out the back. This isn't for use with an

external starter like Indy; it's because the new

seat-back fuel tank prevents. access to the front

of the engine when the mechanics want to turn it over. The 8-in. spacer

casting between engines and gearbox is hollow and does nothing but fill

space, while Porsche on the 908/3 and Alfa Romeo have put their gearboxes in

that empty space, and March tried it on the nix FI car. Coppuck says

the impossibility of changing gear ratios

makes the amid�ships

Late last year Revson's car had cross-drilled

discs. but now they have found the same job can he done by machining grooves

in the disc faces; typically there are three grooves per face running

tangentially out from the hub to the edge. Their function is to prevent both

pad dust and pad material "out-gassing" from interfering with friction. |

|

The new chassis is bent up out of I6- and I9-9auge

aluminum, riveted and bonded to itself as before, but this time the front

suspension loads are taken not with a full steel bulkhead but by small steel

brackets mounted on the tub. Yet the front of the chassis is designed to be

stiffer than before. (There is no front radiator ducting/mounting structure

to absorb collisions.) The shape of the tub is largely determined by the new

radiator location, as fitting big enough cores takes up all the space right

down to the bottom of the chassis. Therefore the outside edge of the fuel

tanks had to be cut away at the rear to form a nice (and very carefully

drawn) smooth air entry. It is this that produced the FI-style "Coke bottle"

shape in plan view. To gain back the lost capacity

an I8-gal. tank was put across the width of the

car behind the driver's seat; it is actually the 5th fuel cell in the

system, into which the other four (two per side) feed, and this new flow

system helps position the several hundred pounds of liquid in the middle of

the wheelbase as it burns off in a race. The new car's body shape looks much like the old and in fact descends directly from it: the technique is to make up one more of the old body in extra heavy cloth, cut it into pieces and drape them over the new chassis, and then fill in the gaps to produce a male buck of the new body. The changes on the M20 are at the sides, where air is induced to flow into the radiators, and at the front where an airfoil rides in the gap between the wheel arches where the radiator ducting used to be-the radiator used to throw its exhaust air upward and produce downforce, but the airfoil does it more efficiently and is adjustable. Both drivers, incidentally, say there is no reduction in the buffeting of their heads from this air flow, but since it's cool air pouring over the top the cockpit is much more comfortable. A neat touch about the new nose is that it hinges up for access; furthermore, the struts that mount the hinge are adjustable for length and allow small adjustments in nose-rake angle. Under the skin probably every piece, familiar or not, has been revised. The "beam," the rear crossmember which carries the top suspension, is much stronger this year and the lower pickup casting is more elaborate to feed the loads into the differential casing more evenly. With stronger U-joints they measure about 0.75 in. wider Denny is content to have his rear brakes inboard again this year. One of the maintenance improvements is the method of mounting the front of the engine: as before it's hung on a plate running across the chassis but this time the plate is actually three pieces butted together with "fish-plates." When changing engines the "fish-plates" are disassembled and the central portion of the main plate, complete with all three pumps, comes out with the engine. It saves a little time, yes, but the mechanics say a bigger bonus is that the pump installation has all been dyno-tested with the fresh engine, so they know it all works and doesn't leak. When testing the prototype M20 a great deal of worry went into getting the radiators to work their best. Several different detail configurations of inlet duct had to be tried before the final arrangements evolved, and the same trouble was caused by getting the air out. Also, the first radiators of aluminum had to be replaced with copper ones-apparently copper can be in thinner sheets and you get more flow through a given size core. Once out in

the world there had to be several significant changes. At Mosport the two

new cars did not go well at all. Part of it was engines, part of it was

tires: Hulme says Mosport proved to him and to Goodyear that the Porsche and

the McLaren need different tires, and part of it was indicated by the

changes made for Atlanta a month later. There were modifications to spring

rates at both ends and the track was widened about 2 in. To be specific,

both cars had spacers of 0.9 in. put under each front wheel, and Hulme's car

had longer links to do the same job at the rear, a job so involved that only

his car was done at that time. By Watkins Glen both cars had the new track

measurements and it was done at both ends by longer links and wishbones.

Brake cooling ducts were let into the front slope of the nose, replacing the

original inlets which had been obscured behind the front airfoil in the

panel ahead of the footwell. Another change was to reposition the rear

airfoil some 6 in. more to the rear; this was done

at Atlanta on Hulme's car in testing and later transferred to Revson's car

to compensate for his not having the wider rear track.

Aerodynamics demonstrated its truly awful power on the 5th lap at Atlanta when Hulme's car flipped backwards like a hydroplane gone amok. Apparently it was a nasty combination of circumstances: he was close behind Follmer in the Porsche, which robbed the McLaren of nose adhesion; he had just gone over the crest of the rise in the back straight and he had just ,hanged into top gear so the nose was pitching up as the clutch gripped. Perhaps, although he doesn't remember anything about he was just then darting out of the Porsche's draft and catching a sudden blast of wind. The combination of effects . as enough to raise the nose into an angle of attack, giving positive lift rather than negative-several hundred pounds of lift Ugly, ugly.

THE THIRD AND fourth races in this year's series were fascinating demonstrations of what people like about motor racing: You never know what to expect. The turbocharged Porsche should have been a cannon on the Watkins Glen straights-but it bombed. The McLarens, bounding back from their debacle at Atlanta, absolutely ran away one-two. Two weeks later the Porsche should have been a terrific handful on the tortuous Mid-Ohio track, but it started from the pole, blew the McLarens off, lasted on dry tires through a rainstorm which had the one surviving McLaren in the pits five times to change tires, and won very convincingly. Nothing is sure about this sport. At Watkins Glen Revson was on the pole (the only driver under the magic I00-sec lap time) but from the first turn Denny stormed ahead and went all the way to the checker. Revvie hung on as best he could and actually set the race lap record. He had some idea of passing the old man to win himself a motor race for a change, but a couple of things held him back. His brakes faded away badly-nobody seemed to understand why-and also he had an aerodynamic imbalance whenever he came close up into Hulme's turbulence. Another super show at the Glen was put up by David Hobbs, who put in a brilliant drive in Steed's Lola and passed everyone but the pair of leaders to hold a solid third, before having to drop back from exhaustion caused by heavy steering and high cockpit temperatures. Francois Cevert took Revson's old M8F ahead to make it McLaren one-two-three. The Shadow had another terrible day, brake trouble holding Jackie Oliver down the field before finally pitching him off into the guardrail and retirement. And the Porsche? Simply put, it was a crock. Evidently the handling was down, perhaps because of tire vibration in conjunction with the lagging characteristics of the throttle response, and apparently the engine was duff: Penske had to use the unfreshened Atlanta motor for Watkins Glen too. In the race several minutes were lost with a problem in the inlet-manifold relief vents, the same thing that caused trouble at Mosport although this time it was simply a broken spring. The Porsche factory had chosen this day to fly over a bunch of European journalists to watch their Panzer crush the Kiwis. It'll be a long time before they do that again. They should have brought them to Ohio instead. Penske took it very seriously, coming early in the week for solid testing with Mark Donohue going around on crutches to help Follmer sort things out. That it all paid off was shown by the Porsche on the pole, a tenth of a second better than Hulme, and by the first lap when Follmer pulled out fully two seconds. He went on from there, spinning twice in the later rainstorm but recovering without losing anything to score L&M's second dark-horse victory on this track. The McLarens were nowhere, Revson having his transmission fail just before the rain and probably being glad of it when he watched his teammate's struggles. Denny finally made five pit stops to change back and forth between wet and dry tires; still he got fastest race lap right at the end and later was able to joke: "After the first stop I reckoned we might as well do some tire testing, Goodyear pays you five bucks a mile for it." The man who won himself some overdue honor was Jackie Oliver, who drove on through the rain like a demon without stopping or even spinning, was electrifyingly fast in the wet, even faster than some people with rain tires, at one stage hauled four or five seconds on a lap in on Follmer, and brought the UOP Shadow home second on the same lap with the winner in Oliver's first finish this year. Milt Minter was almost as fast as Oliver in the rain and even more spectacular, for he spun off twice demolishing the speed trap the second time!-but he gave Vasek Polak's 9I7-I0 another good finish of third. So in four races it was McLaren two, Porsche two, and the ups-and-downs of both marques have given no convincing idea which is the better car.

|

|

|

|

Reprinted from Road & Track November I972 |

gearbox

impractical. The suspension members look as they did before. The geometry

changes are due largely to the different arrangement of components, the

longer wheelbase and wider track and such details as the chassis being about

one inch shallower. The brakes continue trends begun late last season, in

that the front discs are larger instead of being equal with the backs.

gearbox

impractical. The suspension members look as they did before. The geometry

changes are due largely to the different arrangement of components, the

longer wheelbase and wider track and such details as the chassis being about

one inch shallower. The brakes continue trends begun late last season, in

that the front discs are larger instead of being equal with the backs.

Another

change to the aerodynamics was in two stages and was once again aimed at

taming understeer. At Atlanta both

Another

change to the aerodynamics was in two stages and was once again aimed at

taming understeer. At Atlanta both