|

IN

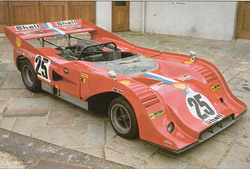

1966, the debut year of the Canadian American

Challenge Cup series - the Can Am for short -

Bruce McLaren's MIB sports cars were outclassed by their more powerful

Lola and Chaparral opposition. In 1972 the M20s lost out in the power

stakes to Roger Penske's brutally fast turbocharged Porsches. In the

intervening years, however, the Can Am was McLaren. The orange

cars from Colnbrook notched up 38 victories, while privateer cars

accounted for two more. Even in that final year of eclipse the works

cars won twice and a private example once, bringing the final marque

tally to an incredible 43.

McLaren himself won the Can Am title in 1967

and 1969, while team-mate Denny Hulme won it in 1968 and salvaged

something from the team's distress by taking his second title in 1970,

the year in which Bruce was killed testing an M8D. Hulme's 1971

team-mate was colorful American Peter Revson, who took the title in the

M8F.

When McLaren began

planning a replacement for the amazingly successful M6A at the end of

1967, the Can Am had already been

dubbed

'The Bruce and Denny Show'. In that year's six-race series Hulme

had achieved a hat-trick and Bruce a brace of wins, only 1966 Champion

John Surtees in a Lola getting a look in at the Las Vegas finale

when the McLaren steamroller ran into trouble.

If the opposition had been trampled into the dust in 1967, it was a

case, in American parlance, of 'you ain't seen nothin' yet' for 1968.

Delays with delivery of the BRM V12 engine

for Mdaren's 1967 M5A GP car had allowed the team to concentrate almost

exclusively on the M6A,which were

consequently tested

exhaustively.

McLaren

had grown eminent in GP racing in 1968 . with the Cosworth-powered M7

A', but the M8As weren't quite so race worthy although they had still

done 500 miles (805 km) running. Similar in concept to the M6A with

bathtub monocoque chassis, the M8A was four inches (10 cm) wider and

comprised a full monocoque using aluminum and magnesium panels bonded and riveted to steel

bulkheads. Its engine was now a stressed member supported by tubular

framework and where the M6A had used 5.8�litre Chevrolet V8s with S20

bhp, the M8A went the whole way with 7-litre unit, developed by Gary

Knutson. These gave 620 bhp, transmitted to the road via a Hewland LG600

gearbox to IS-inch (38 cm) wide Goodyear shod rear wheels. The

suspension followed M6A practice with upper and lower lateral links and

trailing radius arms at the front and a lateral top link, lower wishbone

and twin radius arms at the rear, all allied to outboard coil spring!

damper unite;. Solid disc brakes were replaced

by ventilated units all round.

|

|

In its first race - Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin on 1

September the M8A romped away, Hulme

leading McLaren home in a convincing display that

set the opposition quaking, especially as Hulme broke a rocker arm

part way through and finished on seven

cylinders . .

.

At Bridgehampton they led again, and although they

were sidelined by engine problems, American Mark Donohue (later to

play such a significant role in McLaren's eventual Ca eclipse) won for Roger

Penske in an M6B. At Edmonton he had to be satisfied with third to the M8 ,

Hulme again leading McLaren home, while a torrential rainstorm at Laguna

Seca, and a good wet tyre choice, saw John Cannon win in his aged

Oldsmobile-powered MIB with Hulme second and McLaren fifth.

Victories for

the M8A

Bruce's turn for glory came

at Riverside, where he won the Los Angeles Times

GP from Donohue, with a bodywork damaged Hulme

fifth. Donohue clinched his title at the Stardust GP finale at Vegas, with

Bruce nursing his ravaged car home sixth.

Throughout the series, only Donohue had posed a consistent

challenge through reliability. Both Peter Revson in a Ford powered M6B and

Texan Jim Hall in his Chevrolet-engined Chaparral 2G had been able to match

the M8A for speed on occasion, albeit without reliability.

For 1969 the M8 design was developed to

B specification into what McLaren's Teddy Mayer would later describe

as the team's most successful car.

The spoiler on the

rear bodywork was deleted and replaced by a

strut-mounted overhead aerofoil, the front wheel arches were cut back to

help exhaust air from beneath the nose, and a short stroke, big bore version

of the 1968 engine, now 7046 cc and 630 bhp, was

prepared by George Bolthoff. Testing again began early with a modified M8A

which was converted to full B specification once that had been settled.

In an ill-disguised attempt

to give rivals a better chance of getting on terms with McLaren, the Can

Am organisers had stretched the series from six to 11 rounds, but as

it was to transpire, the Bruce and Denny Show had only been playing in the

provinces in 1967 and '68. For 1969 it made it right to Broadway. In an

unmatched achievement, McLaren won every one of those 11 rounds. Bruce

triumphed in six, Denny five. In eight the 'orange elephants',

as the M8Bs became known were

first and second. At Michigan

Raceway in the eighth race they were first, second and third,

Dan Gurney handling the spare car after Jack Brabham had qualified it. A

year later in less happy circumstances he would again play

a significant role

for the team. . . .

|

|

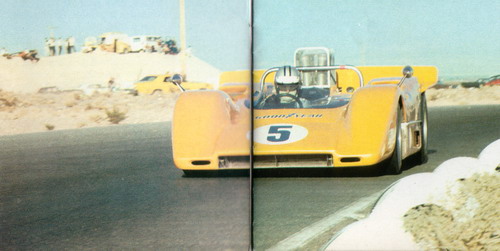

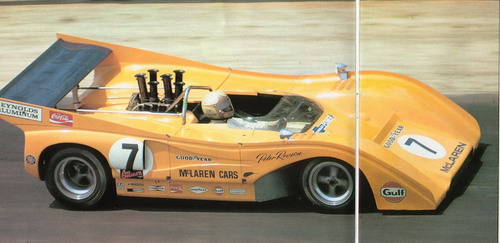

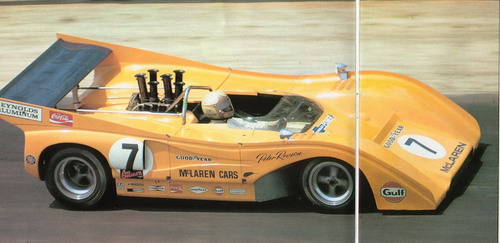

LEFT

Hulme in his McLaren M8D, 1970 LEFT

Hulme in his McLaren M8D, 1970

|

|

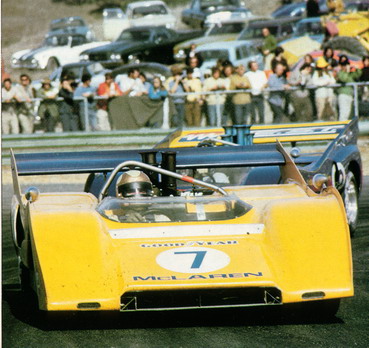

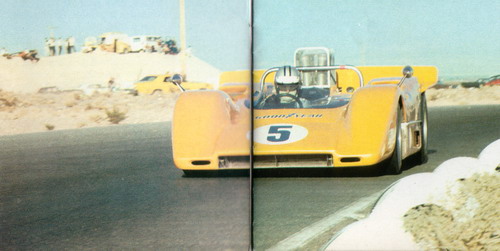

RIGHT

Hulme won this race at

Las Vegas in November

1968, driving the M8A RIGHT

Hulme won this race at

Las Vegas in November

1968, driving the M8A

|

|

While the M8C production version built and

marketed by Trojan in Britain was still a season away in 1969, there were

various customer M6s and M12s, and Gurney tried unsuccessfully to match his

M6B 'McLeagle' on 5.6-litre Ford power against the M8Bs when he wasn't

guesting for Colnbrook. Lola, whose T70 had won

Surtees the first

Can Am

title in 1966, had had a poor 1968 with the T160 and didn't fare much

better with its development T162/163 models, while Ferrari, having raced

sporadically in 1968, ran Chris on in a

developed version of the 612 six-litre V12 car

at he had driven in the last round the previous year The former McLaren driver finished third on his debut at a 'ns Glen

and created a sensation by leading Hulme at the next race at

Edmonton before finishing only

five seconds

in arrears. Thereafter, though,

the Italian thoroughbred proved breathless

with its litre

disadvantage and never again posed a real threat.

After it broke its engine at Laguna

Seca practice McLaren offered his old employee a ride in the spare M8B

but with typical Amon luck

its differential broke. The

narrow-track Chaparral 2H for Surtees was a total disaster,

proving that even Jim Hall could

make mistakes, while

Jack Oliver's Peter Bryant-designed Autocoast

Ti22 ( type numbered after the chemical

symbol and

valency of the titanium from which it was

made) showed late series promise. The car that caused the greatest

interest, however, and which would

ultimately prove the most significant newcomer from McLaren's point of

view, was the 4.5- then 5-litre Porsche 917 Spyder

driven by Jo Siffert. He had a few

reasonable placings but, like on, suffered from a capacity deficit,

proving the American adage that there

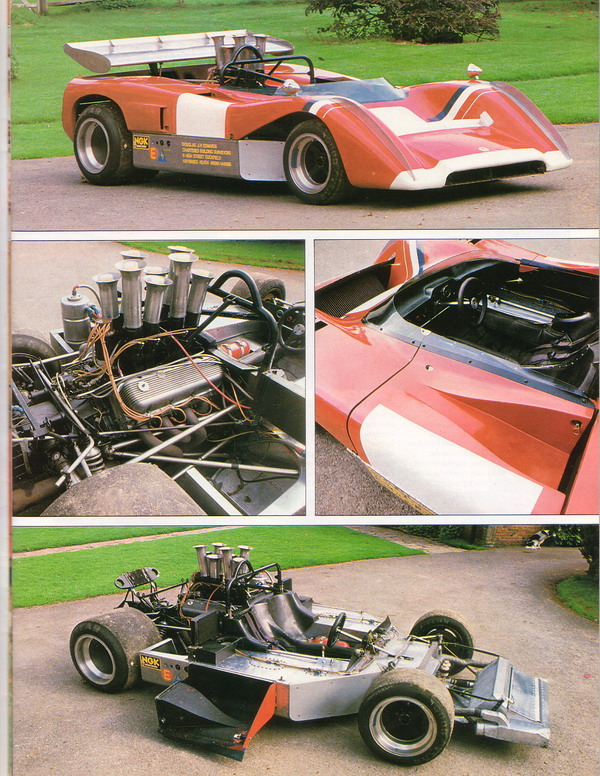

Revson's 8F, at Laguna Seca in 71

year The former McLaren driver finished third on his debut at a 'ns Glen

and created a sensation by leading Hulme at the next race at

Edmonton before finishing only

five seconds

in arrears. Thereafter, though,

the Italian thoroughbred proved breathless

with its litre

disadvantage and never again posed a real threat.

After it broke its engine at Laguna

Seca practice McLaren offered his old employee a ride in the spare M8B

but with typical Amon luck

its differential broke. The

narrow-track Chaparral 2H for Surtees was a total disaster,

proving that even Jim Hall could

make mistakes, while

Jack Oliver's Peter Bryant-designed Autocoast

Ti22 ( type numbered after the chemical

symbol and

valency of the titanium from which it was

made) showed late series promise. The car that caused the greatest

interest, however, and which would

ultimately prove the most significant newcomer from McLaren's point of

view, was the 4.5- then 5-litre Porsche 917 Spyder

driven by Jo Siffert. He had a few

reasonable placings but, like on, suffered from a capacity deficit,

proving the American adage that there

Revson's 8F, at Laguna Seca in 71

is

no substitute for cubic

inches. Later Porsche would add its own rider

to . that, to the effect that there was no substitute unless you had a

turbocharger. , . ,

With

the train running smoothly on its rails, McLaren spent the winter

perfecting the latest M8 derivative, e M8D. F ban on strut-mounted wings

saw the rear bodywork sprout attractive fins

between which a low wing was slung, and as the existing tubs were

retained, albeit with 4�inch wider suspension, the wider

bodywork

curved in neatly where it rested atop the chassis.

Bolthoff overstretched himself and the engines by trying an 8-litre 700

bhp version in tests, and when this monster exhibited

self-destructive traits, 7620 cc units were substituted, These developed

670 bhp at 6800 rpm and a massive 600 lb ft of

torque. This was thought to be sufficient.

Development of

the M8E

On 2

June 1970, at Goodwood, McLaren was conducting routine testing in

Hulme's intended race car when a tail securing pin went missing.

Wind pressure ripped away the rear

bodywork

and wing and, devoid of

its downforce, the M8D slid broadside into a

marshal's post at well over 100 mph (161 kph). Bruce McLaren,

just short of his 33rd birthday, was

killed.

.

As

a man he had always had the respect of his fellows and race

enthusiasts the world over; as a combination of driver and brilliant

engineer/designer he had no equal. Understandably the

team took his death very badly, but somehow it kept going, its

plight made no better by the severe burns Hulme's

hand had sustained when his ride for the

Indianapolis 500 caught fire.

'The Bear' was teamed with Dan Gurney

when the shattered Colnbrook equipe faced the

starter at the first 1970 Can Am race at

Mosport 14 June. Dan took pole but both

M8D drivers got a fright from Oliver in the

Autocoast; a controversial incident between Oliver and privateer Lothar

Motschenbacher in the lapped M8A-based M8B let Gurney get clear to win,

but the Ti22 was quick enough to stay ahead of the injured Hulme. Gurney

won again at St Jovite while Denny took his

turn at the next three venues. By Elkhart Lake in August Gurney had been

obliged to quit because of contractual clashes but F5000/F1 McLaren

pilot Peter Gethin was drafted into his place and won. At Road Atlanta

it finally seemed that McLaren had met some worthy opposition when Vic

Elford made his debut in the innovative Jim Hall Chaparral 2J which

Jackie Stewart had driven earlier at Watkins Glen. 'Quick Vic' took pole

position in the boxy white device which used a small auxiliary engine to

suck the air from beneath its skirted chassis to produce ground effect

and phenomenal adhesion, much to McLaren's consternation. In the event

the 2J broke and both M8Ds crashed, victory falling to Tony Dean's

outclassed private Porsche 908.

Thereafter the series was dominated by

Hulme, but the paralysing speed of the Chaparral continued to turn cold the marrow of the Colnbrook team's bones. At the Riverside finale it was

on pole by two

whole seconds,

(most runners would have given their eye teeth to pip a

McLaren to pole by two tenths) and the protests began to fly.

Eventually, to Hall's disgust, the 2J was outlawed. But if that produced

a huge sigh of relief at McLaren the future was only partly rosy. After

a backflip at St Jovite, Oliver proved an M8D

baiter in the Ti22, while Peter Revson had proved quick, especially at

Donnybrooke where he ran Hulme close from pole position, in the Lola

T220. At least one potential enemy was converted to ally status when

Revson was signed to partner Hulme for 1971, but the downside was that

Stewart would replace him at Lola, where an all-new bullet-nosed T260

was taking shape.

the marrow of the Colnbrook team's bones. At the Riverside finale it was

on pole by two

whole seconds,

(most runners would have given their eye teeth to pip a

McLaren to pole by two tenths) and the protests began to fly.

Eventually, to Hall's disgust, the 2J was outlawed. But if that produced

a huge sigh of relief at McLaren the future was only partly rosy. After

a backflip at St Jovite, Oliver proved an M8D

baiter in the Ti22, while Peter Revson had proved quick, especially at

Donnybrooke where he ran Hulme close from pole position, in the Lola

T220. At least one potential enemy was converted to ally status when

Revson was signed to partner Hulme for 1971, but the downside was that

Stewart would replace him at Lola, where an all-new bullet-nosed T260

was taking shape.

|

|

The showdown with mighty Porsche

Through 1970 Hulme had actually tested what at the time was dubbed the

M8E, which was intended to spearhead the 1971 programme, but that

designation eventually went to that year's Trojan customer car and the

works car became known as the M8F. This was similar to the D save for

full-length fences along the upper bodywork to . promote more downforce,

and 8. I-litre Chevy engines prepared once again by

Knutson. With aluminium cylinder blocks courtesy of sponsor

Reynolds, power was again increased to an incredible 740 bhp.

Where the M6A had been the design work of Robin Herd, and the M8A

that of Swiss engineer Jo Marquart, in collaboration with Bruce, the M8F

was the work of McLaren stalwart Gordon Coppuck. This time the changes

included a longer wheelbase, inboard rear brakes to reduce unsprung

weight and a stiffer chassis. Once again the . old cars were sold off to

privateers, while sundry new M8Es were sold.

The new season began with a shock, as

Stewart planted the Lola on pole at Mosport on 13 June and led

prior to gearbox problems. That left Denny to lead Peter home, a pattern

repeated at St Jovite and reversed at Road

Atlanta and Watkins Glen. However, Stewart continued to be a thorn in

the McLaren flank and duly won at Mid-Ohio when both M8Fs broke CV

joints. Revson won at Elkhart Lake but Stewart was again quick, as was

Oliver who was now in an unreliable Shadow. Revson won twice more, in

convincing style at Donnybrooke and under a cloud at Laguna Seca where

he ignored the black flag in the closing laps when leaking oil. Denny

then endorsed the McLaren domination by taking the remaining races at

Edmonton and Riverside, although he couldn't quite amass enough points

to hang on to his title, which passed to the deserving Revson. As a sign

of the opposition's desperation, sabotage was suspected at Edmonton when

a bolt was found in one of the injection trumpets on Revson's car. He

was obliged to start late while it was fished out. . . .

Thus ended the season in which the team had

faced real opposition on a consistent basis. Ultimately, although

Stewart had frequently led, the McLaren proved the better, more reliable

car; Lola was handicapped, however, by having only a single car entry.

|

|

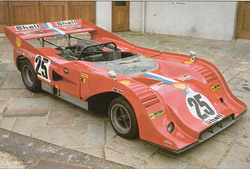

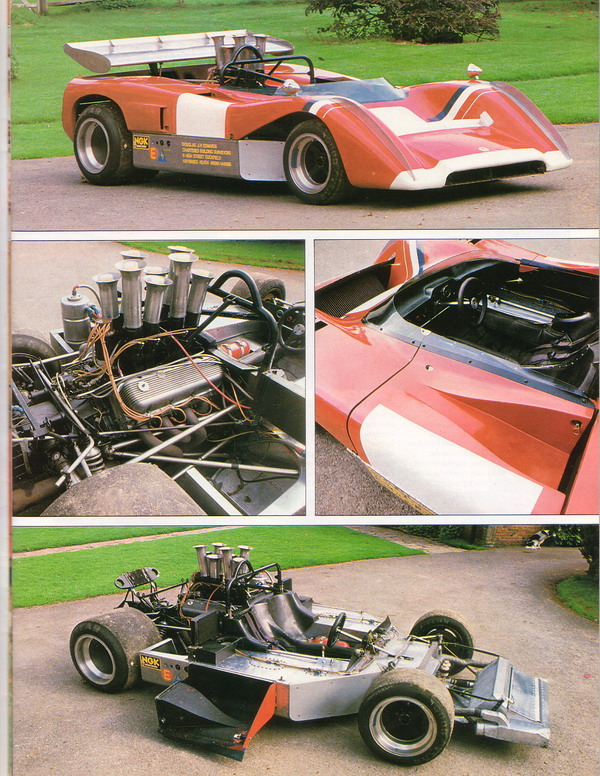

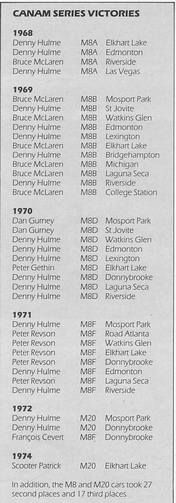

Views of another ex- VDS, ex

Johnny Jordan McLaren M8E, used in both

CanAm and lnterserie racing.

For many years this car held the lap record at Silverstone: 50 seconds

dead |

|

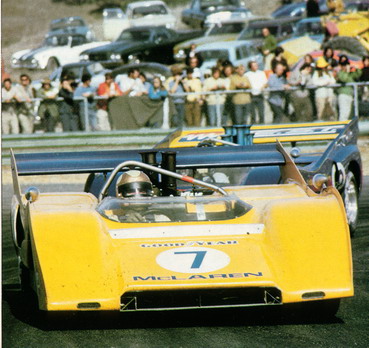

Peter Revson driving his M8F in 71 |

|

McLaren's fatal crash

Then came the news that Porsche would mount

an all-out challenge for the 1972 CanAm, and would have its efforts

managed by the highly professional Roger Penske for another skilled

driver/engineer, Mark Donohue. At last, after so many years of fighting

paper tigers, the showdown had arrived. The

CanAm town would ultimately prove big enough for only one of them.

Coppuck's response was an all-new McLaren,

the attractive M20.

To

pack as much weight within the wheelbase for a low polar moment of

inertia, he moved the water radiators to the sides, supplemented the

usual sill fuel tanks with one behind the seat, and stretched the

wheelbase to 100 inches (254 cm). Suspension

remained much as per M8F but the bodywork was

neater and an aerofoil was slung between the two front wings. In

testing, the car was quick, and won praise

from drivers who appreciated the fact that cockpit heat from front

radiators was now a thing of the past. To

pack as much weight within the wheelbase for a low polar moment of

inertia, he moved the water radiators to the sides, supplemented the

usual sill fuel tanks with one behind the seat, and stretched the

wheelbase to 100 inches (254 cm). Suspension

remained much as per M8F but the bodywork was

neater and an aerofoil was slung between the two front wings. In

testing, the car was quick, and won praise

from drivers who appreciated the fact that cockpit heat from front

radiators was now a thing of the past.

First blood at Mosport

McLaren's other secret weapon for 1972 was a

deal with Jackie Stewart but when he had to pull out due to a stomach

ulcer, Revson was asked to. combine the CanAm with his McLaren

commitments in USAC.

It was Hulme who drew first blood at Mosport

on 11 June, baptising the M20 with

a lucky win. Donohue had run into trouble but staged a fine

recovery and just failed to pip Denny's sick car.

Revson was third. At Road Atlanta, Donohue was

replaced by George Follmer after a huge testing shunt and while the

American sped to an early debut win, Hulme

back flipped at 190 mph (306 kph). He escaped with no real injury, while

Revson set a new lap record but retired with

no oil pressure. At Watkins Glen it was Follmer's turn for trouble,

Hulme heading Revson for an M20

1-2

with Francois Cevert third in Greg Young's ex

Revson M8F. Then, for the first time in a long while, the works McLarens

were soundly thrashed at Mid-Ohio. Follmer

won, Oliver was second in a new Shadow and

Milt Minter's Porsche beat Hulme for third. Follmer won again at Elkhart

Lake after polewinner Hulme suffered ignition failure. Revson had a dud

clutch, but Cevert was second despite a sick engine. 1-2

with Francois Cevert third in Greg Young's ex

Revson M8F. Then, for the first time in a long while, the works McLarens

were soundly thrashed at Mid-Ohio. Follmer

won, Oliver was second in a new Shadow and

Milt Minter's Porsche beat Hulme for third. Follmer won again at Elkhart

Lake after polewinner Hulme suffered ignition failure. Revson had a dud

clutch, but Cevert was second despite a sick engine.

Worse was to come,

for Donohue was out of hospital for Donnybrooke, ready to back series

leader Follmer. A ferocious duel saw the M20s stay with the turbo

Porsches until the British cars blew their engines; Donohue then blew a

tyre and Follmer ran short of fuel on the last lap. Through it all, like

a knight on a charger, came Cevert to win.

The writing on McLaren's wall

That, however, was to be McLaren's

43rd and last CanAm win. Donohue won at Edmonton after Hulme led

for a while, could have done so at Laguna Seca but slowed to let Follmer

through to clinch the title, and then had the compliment returned

at Riverside only to pick up a puncture, handing George his fifth win.

The writing on McLaren's wall said only one

thing: get out of town.

The M20s could often match the fast

Porsches' practice pace, but come the race

reliability lay with the German cars. The M20s either had to run off

pace with detuned engines, or risk mighty breakages if they tried to

match their rivals' power advantage. Hulme frequently bitched about

screwdriver-tuning for extra power, something that would eventually

become familiar in the GP world where, ironically, turbocharged

McLaren-Porsches would prove so successful.

Private McLarens appeared in the 1973

CanAm and Europe's Interserie equivalent, but the works cars never raced

beyond 1972. In the last CanAm race of 1974 at Road

Atlanta, Scooter Patrick had a lucky win

in an . ex-works car after Jackie Oliver's Shadow

blew up. They had had their period of dominance - one of the longest in

any professional racing series

- and had in

turn been dominated. Neither Teddy Mayer nor Phil

Kerr of McLaren felt inclined to try matching Porsche's

vast budget in the development of

turbocharging and as Denny Hulme finished runner up to George Follmer in

that 1972 series, the end was finally written to an outstanding chapter

in road racing. Thereafter McLaren concentrated on the high-power arena

of Formula One. |

|

the marrow of the Colnbrook team's bones. At the Riverside finale it was

on pole by two

the marrow of the Colnbrook team's bones. At the Riverside finale it was

on pole by two

To

pack as much weight within the wheelbase for a low polar moment of

inertia, he moved the water radiators to the sides, supplemented the

usual sill fuel tanks with one behind the seat, and stretched the

To

pack as much weight within the wheelbase for a low polar moment of

inertia, he moved the water radiators to the sides, supplemented the

usual sill fuel tanks with one behind the seat, and stretched the

1-2

with

1-2

with